2.1 Active & Passive Beats

An active beat is one which is intended to generate a response. This can be as basic as knowing when to play, or it can be information about dynamics, articulation, change of tempo or many other things. A passive beat is one which is intended to give information, but not to result in an immediate response.

A good example is the number of preparatory beats the conductor indicates before the music begins. As a starting point, we should aim to give only one gesture as this will often prevent confusion – the more we do, the more chance there is that someone will misunderstand us – and prevents the impression that we are micro-managing or don’t trust the musicians. However, in many cases we will need to give more information than that, usually to help the musicians be clearer about the tempo. This can simply be because the tempo is quick: once you get faster than around 120 beats per minute, there will often not be enough time for everyone’s brain to compute the tempo with sufficient certainty.

Therefore, the conductor will need to give 2 preparatory gestures. This spells danger! The way to avoid any accidents is to make sure that only the last gesture before the musicians play is active. Everything before that should be passive. One way to think about the difference is that an active gesture begins with a noticeable impulse, a passive gesture does not. Watch this short video which has a couple of examples of a passive first beat, followed by an active second beat.

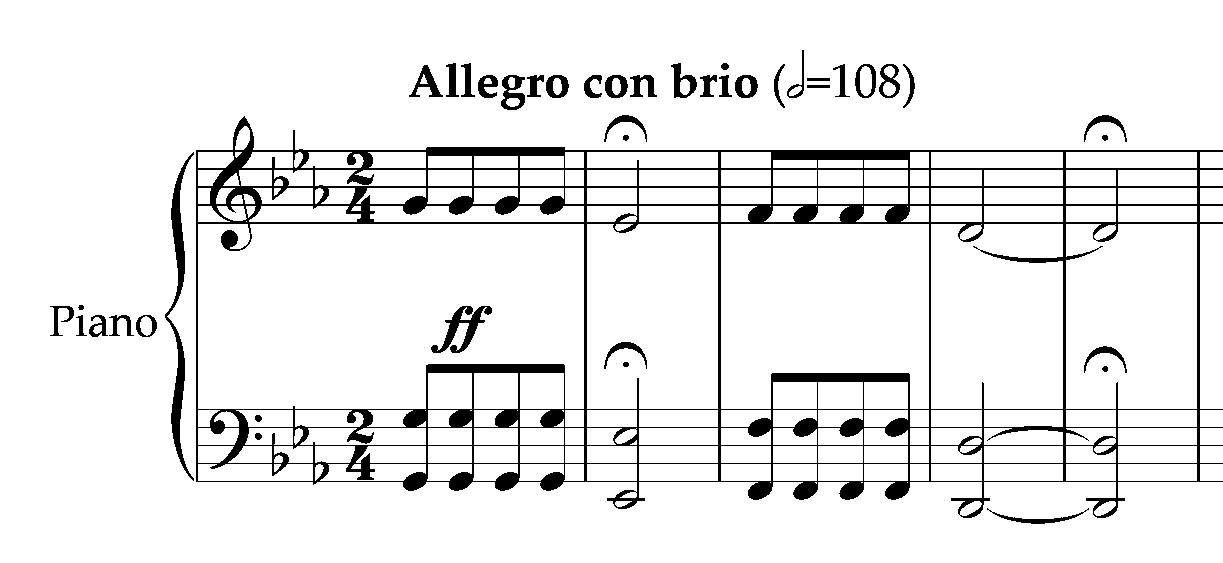

The most extreme example of this is the famous opening to Beethoven’s Symphony No.5. If Beethoven had written this there would be no problem:

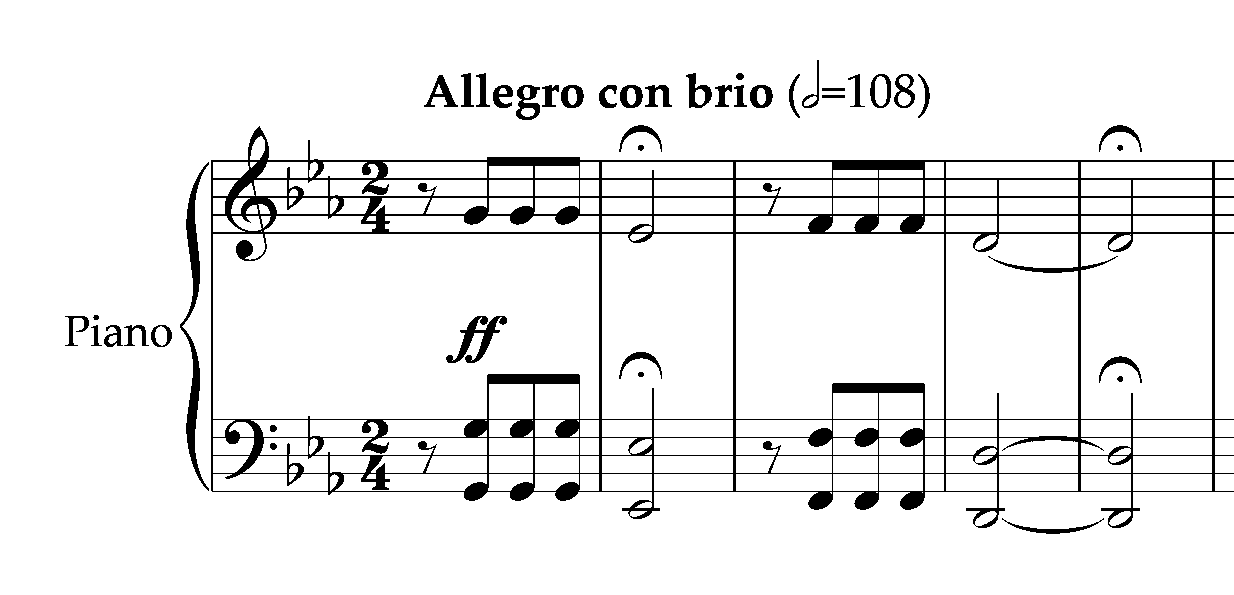

The conductor gives a nice energetic impulse and the orchestra plays one measure after that impulse. However, of course he wrote this:

The combination of the music being in one, together with the eighth note rest, creates fabulous possibilities for confusion! When the conductor gives an active impulse should the orchestra play after an eighth note, or after one measure plus an eighth note? Orchestras are often forced to take matters into their own hands and make that decision for themselves! The trick is to make sure there is no impulse at the beginning of the preparatory beat – this prevents anybody jumping in early. You could think of this as pulling a catapult rather than bouncing a ball. The tempo can still be communicated, and the active impulse that comes with the next gesture tells the orchestra to start. In this video the conductor gets it wrong the first time, and right the second time!

A further area where passive beats can be useful is in marking silence. Conductors must always remember that (with the exception of choirs) the players don’t usually have the full score. Their own individual part is unlikely to tell them whether rests are for everybody, or just them or their section. Quite literally, it can sometimes be difficult to know which measure you are in. It is generally good practice to indicate rests with passive beats. A good example of this is in operas or concerti. If the soloist has four measures to play or sing with no accompaniment, the conductor might show four passive downbeats to indicate the geography. This doesn’t need to be done in tempo or with whoever is singing or playing, it is purely practical information.

In this extract from Verdi’s Overture to La forza del destino the notation is potentially confusing. After the fermata bar, anyone not playing the melody could be in doubt as to whether that begins in the upbeat to the Andantino, or the upbeat to the following bar. In the video you’ll see that the conductor makes this clear by passively indicating beats 1 & 2 before giving a more active gesture on the third eighth note to instigate the entrance.