2. Orchestral Scores

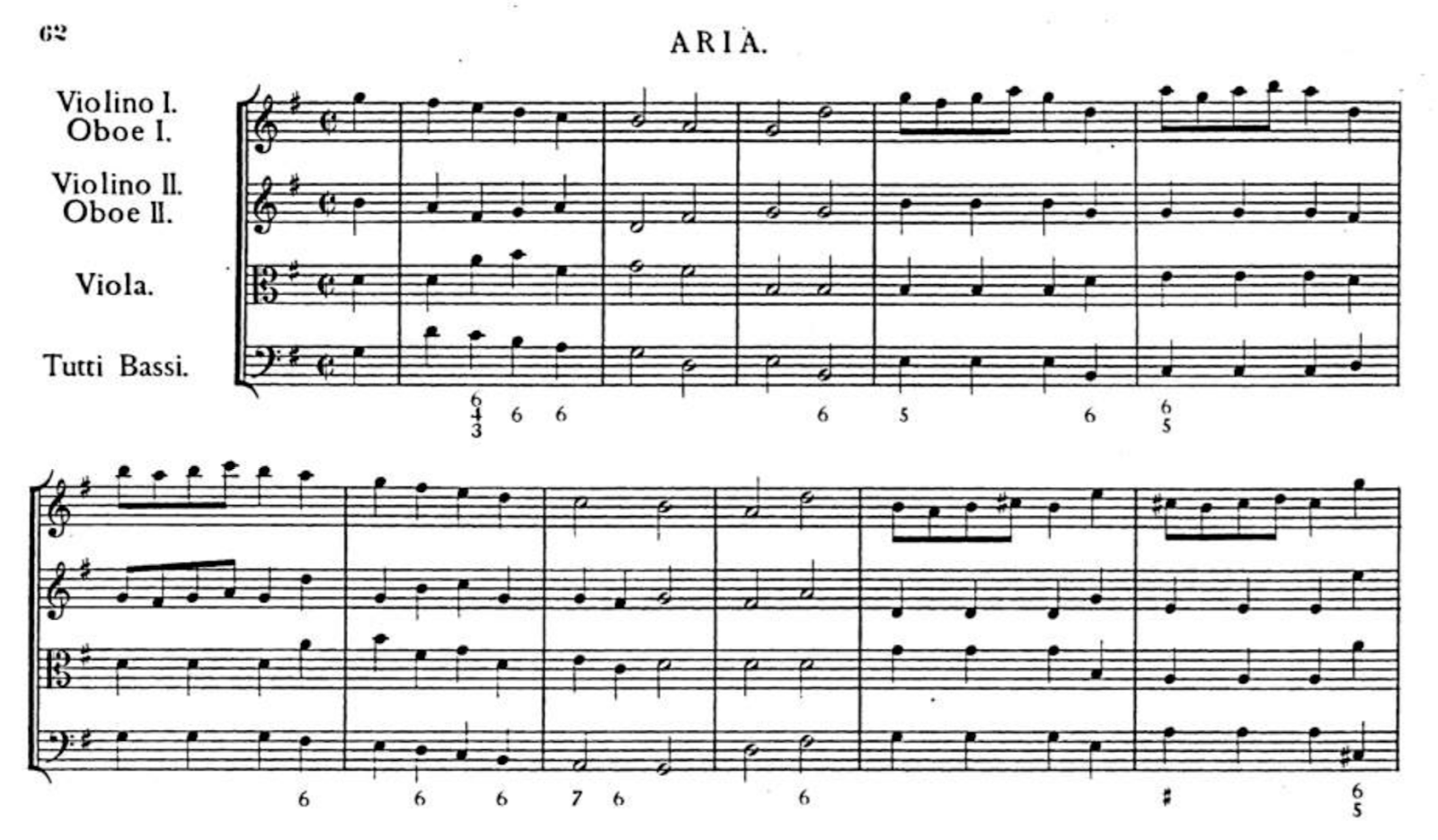

Orchestral scores began to develop in the Baroque period, as the orchestral body started to take shape after the adoption of strings became the core of instrumental music-making. Wind instruments were added to the strings sporadically, depending upon which instruments were available for a particular performance and upon the wishes of the composer. Thus the organising of the scores themselves varied in terms of the vertical arrangement of the different parts. It was common for instruments, such as oboes and violins as seen in Example 1, to share the same staves as they shared the same music. Baroque orchestral scores usually include notation for the basso continuo written below the bass line.

Example 1: Handel, Water music, Suite no.3 in G major, HWV 350: Aria-Rigaudon

The more standardised symphony orchestra did not emerge until the end of the eighteenth century. While some scores of the late Classical period, especially the manuscripts, still show some variety in the layout of the instruments, the fledgling music publishing industry began to standardise orchestral score formats. The modern layout placing the winds above the strings, and with instrument groups organised from higher-pitched instruments to lower-pitched instruments emerged at this time. It was also common, even in the eighteenth century, to have the cellos and double basses written on the same stave.

Today, modern scores are organised with woodwinds on top, followed by horns, then brass, then percussion, harp, piano, and the string parts at the bottom.

In larger works, empty staves are often hidden to save space. In works from the 20th century, it is also common for composers and publishers to indicate if the score is transposing or non-transposing. This is to avoid doubt for the conductor, especially where there is no key signature or when the music is atonal.