3.1.2 Rehearsal for choirs

Score Preparation

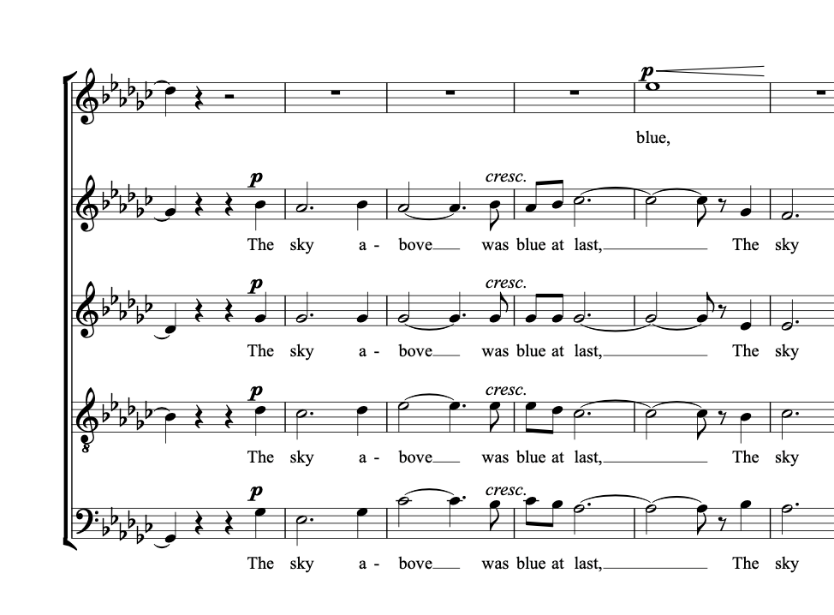

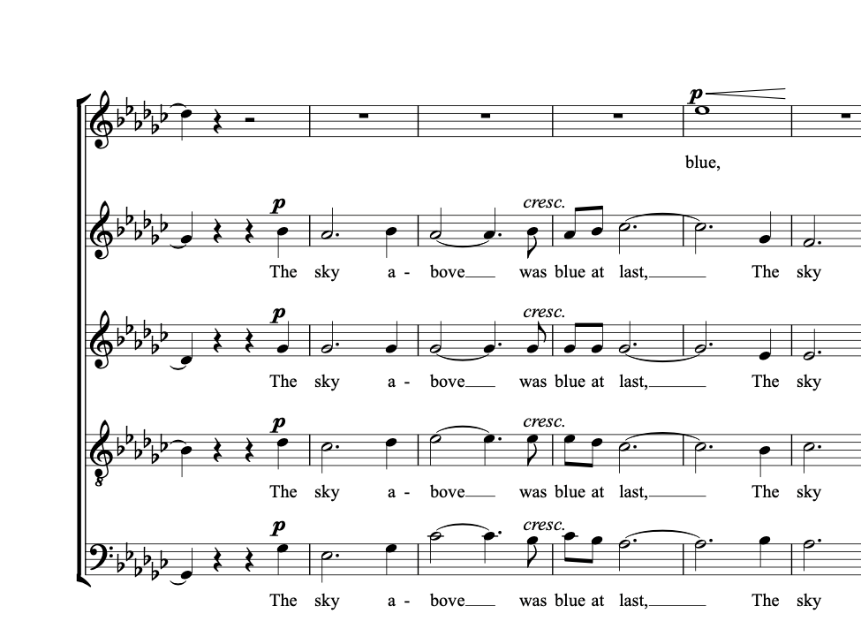

Before you turn up to your rehearsal, you will have prepared your score. When we mark up a choral score, we should also consider where the singers will need to breathe. You may need to choose the moments where the singers should shorten a note to take a breath and decide how long that breath will last (often it’s simply a matter of taking out an eighth note). This is particularly important for words that end with a hard consonant, as the choir needs to place that consonant together. For example, in this excerpt from Stanford’s The Bluebird, we might like the singers to breathe after the word ‘last’ in measure 5 to acknowledge the comma in the text:

This will work if we take an eighth note out of the tied dotted half note and place the ‘st’ of the word ‘last’ a little early. The music will now sound like this:

In rehearsal, try to show where these breaths are with a gesture as you sing through the music – this saves time talking about them. A slight click and lift of your arms within the beat pattern can easily show that the choir should lift their sound and take a breath. If it’s not obvious on the page or the choir didn’t notice your gesture, then a swift explanation will be necessary.

There may also be points in the music where you specifically do not want the choir to breathe. In the example above, you might decide you do not wish to acknowledge the comma in the text, but instead would like to keep the sound going all the way through. A left-hand sweeping gesture can show a ‘going through with no breath’ moment.

Logistics

A favourite choral question is ‘When do we stand and sit during the concert?’ It might seem insignificant, but often the choir must stand up during an orchestral introduction or interlude and it is incredibly embarrassing for the singers, and distracting for the audience, if half of them get it wrong! Allow 10 minutes before concert day to go through all the Stands and Sits in a concert. Within a large work ask your singers to mark these in their score.

Language

You will often be dealing with text in a different language to your native tongue. If you are working at a professional level, a language coach may be available to work with the choir during your rehearsal (accept the offer of this unless you are absolutely assured of your ability to pronounce the language). Of course, you must factor this into your rehearsal time and keep things moving efficiently and effectively whilst being courteous. In general, it would be a good idea to get to grips with the Latin text of the Mass and the Requiem Mass; you won’t get a language coach coming in for Latin (they’re all dead now). If you aren’t lucky enough to have a language coach on offer, see if a friend or colleague with relevant expertise might read the text through, and talk you through the pronunciation rules for that language. You don’t need to learn the whole language; you just need to be able to read and pronounce the words of the piece for your choir.

It’s vital to know what the text means. Writing a literal translation in your score, word for word, is the best way to go about this. It’s worth going through the literal translation as you rehearse the piece, or having printed copies for the choir so that they know too.

Pitching

Remember that a singer always has to carefully pitch their notes unless they have perfect pitch; it’s not like pressing buttons on a wind instrument or pressing a string on a string instrument – there’s no guarantee that the right pitch will come out every time! (Of course, professional singers will rarely make pitching errors, although in extremely complex music, they may need time working on the notes).

Whenever we begin a piece in rehearsal or concert, we must give the singers a pitch or a chord. It can be useful to have a pitch pipe if you are working without an accompanist so that you don’t waste time going to and from the piano (unless you have perfect pitch yourself). You should also give a new pitch/chord each time you re-start in a rehearsal.

With an amateur choir, you may need to spend a good deal of time learning the notes. Try to avoid ‘note-bashing’ call-and-response rehearsals in which the accompanist plays a vocal line and the singers sing it back. This only works with one or two voice parts at a time, so it wastes valuable rehearsal time for the rest of the choir. In general, this is an ineffective method of getting the pitch into the choir’s memory, and over a long period of time, does nothing to improve the sight-singing technique of the choir. Instead, try to incorporate note learning into your rehearsal of the musical detail.

For example: the choir sings a phrase with a number of pitch errors, we immediately stop and repeat that phrase in quick succession three times. You may like to phrase it like this:

- ‘OK everyone, let’s sing that phrase again, this time with a much more dramatic crescendo.’

- ‘Great, let’s sing that phrase again, this time focussing on the final consonant being together.’

- ‘And one final time, this time with a mysterious character!’

After this, you may find the notes are now correct and you’ve also added some exciting musical detail – a triumph! If the notes still haven’t improved, then you might consider looking at an individual voice line and asking the accompanist to play just their line with them as they sing. In this case, ask the accompanist to play the line in two hands, one doubling an octave higher or lower – this makes it easier for a singer to hear it whilst they are also singing.

Rehearsal planning

As already touched on in Rehearsal Chapter 1, we might consider sending some voice parts home early and working with just part of the group for the last part of a rehearsal. It can be useful to hold sectional rehearsals (just the sopranos and altos or just the tenors and basses) at the beginning of a run of rehearsals, particularly for an amateur or young choir. In some circumstances, if you’re willing to lead from the piano and your accompanist is also happy to lead a sectional from the piano, you can end up doubling the rehearsal time by splitting off into separate rooms for a simultaneous rehearsal.

Structure your rehearsals effectively bearing in mind the vocal health of your choir. For example, don’t keep asking the sopranos to repeat a very high phrase over and over again! Often an amateur choir might invite an orchestra and professional soloists to turn up only on the day of the concert; plan this on-the-day rehearsal in a very detailed way – you have to stick to your schedule and you will probably have to cover all of the repertoire for the concert. The orchestra and soloists need most of your attention in this rehearsal, as they may be sight-reading. However, you need to keep your choir happy and enthusiastic as it is ‘their’ show! The choir should be confident with the music by the day of the concert, but the sound of an orchestral accompaniment, as opposed to a piano accompaniment, can be an added challenge. Think about how your gesture can keep the singers’ confidence up and keep them at the front of the beat; a common problem is that the choir will sing late, behind the orchestra.

Non-professionals

As we saw in Rehearsal Chapter 2.2, there are different approaches to working with different types of groups, eg. Amateur, professional or student.

The amateur choral world is hugely important across the globe. In some countries, grass routs choirs are the real backbone of the choral world, not least in the UK. In some countries, a professional symphony orchestra will engage an amateur choir. Unpaid for their performance, but still performing at a professional level.

With amateur singers and young singers, it is important to keep vocal production healthy and to offer tips and suggestions for their vocal technique during rehearsals. For example, simply checking in with how your singers are sitting on their chair in rehearsal can be vital for improving their pitch. It’s easy to slump in chairs as the rehearsal goes on and the singers get tired. Remember to regularly ask the choir to stand up during the rehearsal, especially if you are going to run a longer passage. With professionals, of course, you would not offer technique suggestions and they know when they will stand or sit during a rehearsal/recording.

Psychology

The voice is completely bound up with the human being it belongs to! A very important part of conducting choirs is working with the psychology of the room and keeping the confidence levels high. It may seem obvious, but a negative, aggressive, or nervous attitude will have a direct effect on the sound that’s being produced in front of you. Bear in mind the nerves of a vocal soloist; stay positive and make sure any criticism is constructive and useful. It is not helpful to throw a tantrum on concert day to a group of amateur singers who haven’t quite got all of the notes right yet!