1. Using Transpositions

Transpositions are not difficult if one keeps in mind two primary issues:

- The pitch that is actually sounding, often called concert pitch

- The written note the player is seeing and therefore fingering

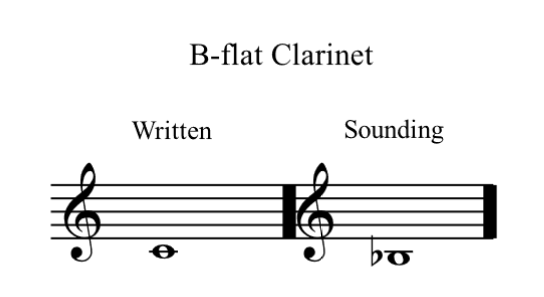

The most important thing to determine is which pitch is the written pitch and which is the sounding pitch. Use the B-flat clarinet as an example. The clarinet fingering a C will sound its name, which is B-flat. The interval of transposition is a major second lower. Once that is known, transposition can be worked out from sound to notation or vice versa. The interval of transposition indicates that any pitch played by the B-flat clarinet sounds a whole tone lower. This also applies to the key signature, thus a piece in which the clarinet plays in C major will sound in B-flat major. The conductor needs to be alert to key signatures for transposing instruments and also to take special care when accidentals are involved as either the written or the sounding pitch may have a different accidental or no accidental.

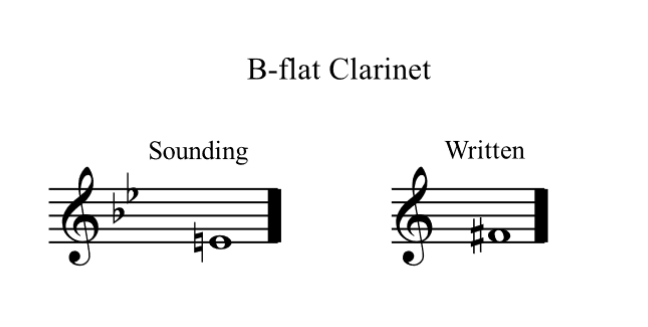

We need to take extra care when dealing with accidentals. If there is an accidental in the original part, then there must be an accidental inserted into the same location of the new part. However, it might not be the same kind. For instance, a natural sign in the original part may become a sharp in the new part:

To avoid confusion and mistakes, think through the process in an orderly way and avoid guesswork.

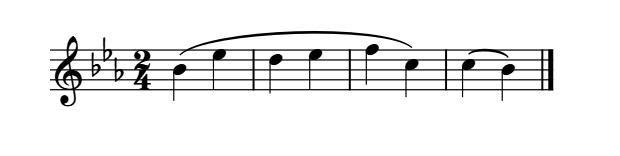

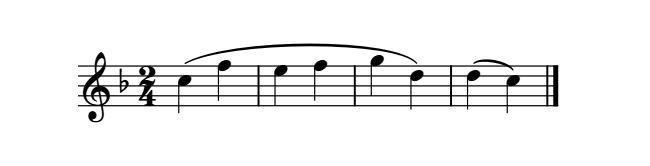

Examples 1 and 2 show a brief extract from Beethoven’s Fifth symphony in which the clarinet and violin answer each other at the same pitch.

Note that the clarinet part takes the key signature and the notes up a whole step from C minor to D minor in order to play at the same pitch as the violin. The same process would be required for the clarinet to play in unison with a piano.

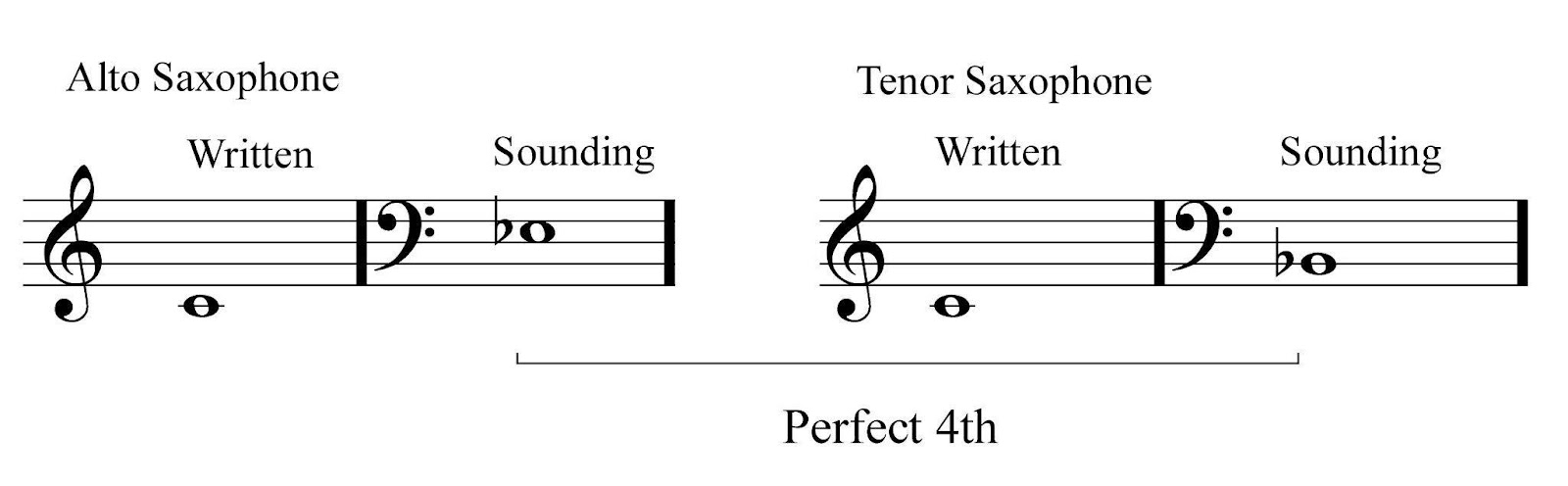

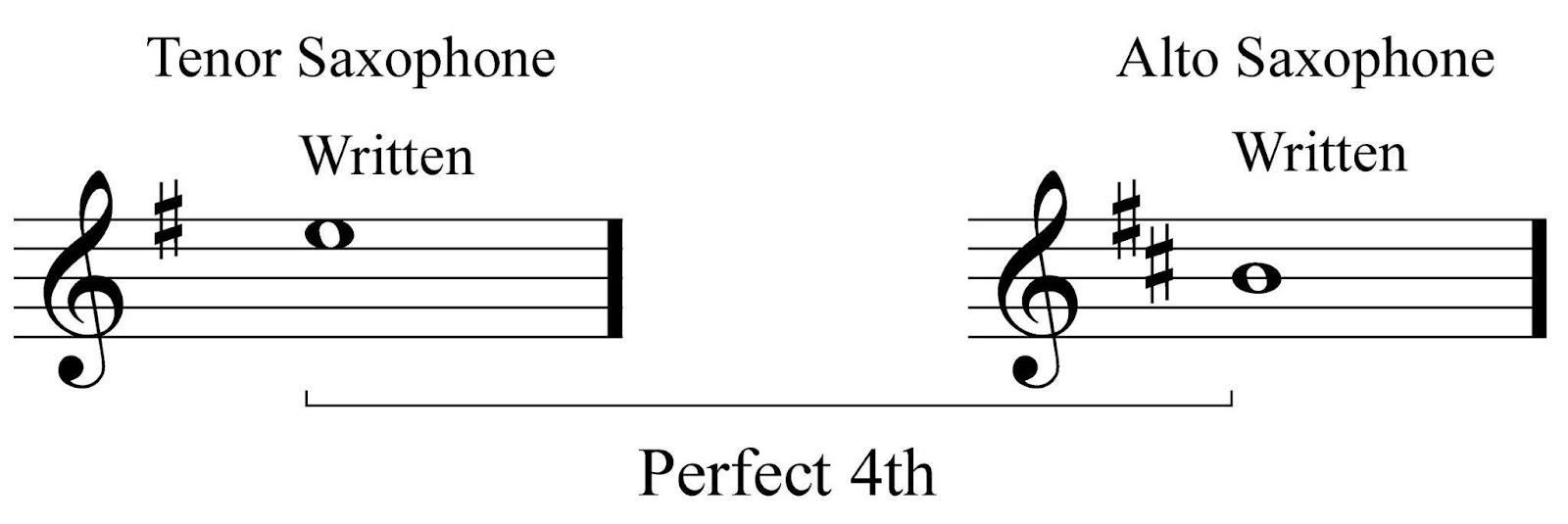

Another transposition scenario involves relating one transposing instrument to a different transposing instrument. If an E-flat alto saxophone had to play in unison with a B-flat tenor saxophone, it would be cumbersome to transpose first from E-flat to sounding pitch, and then transpose again to the B-flat pitch. This would also double the chance for errors. The best way is to utilise the same method involving the interval of transposition. An alto saxophone playing a C (written note) sounds the name of the instrument (E-flat) and the tenor saxophone playing a C sounds (written note) the name of the instrument (B-flat). By comparing the E-flat and B-flat, we can determine that the interval of transposition is a perfect fourth. In this case, to match the two instrument sounding pitches, the alto saxophone must take the key signature and the written notes of the tenor saxophone down a perfect fourth.

For a practical example, imagine the tenor saxophone has an E written on the 4th space and is playing in the key of G Major. To match this with the alto saxophone, you would need to play down a 4th, so a B on the 3rd line, and transpose the key to D Major.

When notating a transposition, the new part should not use enharmonic pitches. For example, a whole step lower from G-flat must be written as F-flat rather than E-natural. All the accidentals must be transferred correctly to the new key.

Certain transpositions are used much more frequently than others. In wind and brass bands, the primary keys are B-flat, E-flat, and F while in orchestral scores, B-flat, F and A are the most common. It’s worth remembering though, that when dealing with horn and trumpet parts from music written before the 20th century, these may be in almost any key! When dealing with transposition it is not only the key of the particular instrument that is important but also the octave or the direction of the transposition: if it transposes up or down.

As a rule, all of the alto, tenor, baritone and bass register instruments transpose down while the soprano instruments are likely to transpose up if they are in E-flat or D but down if they are in B-flat or A. As usual, horns have their own rules and can be either!